Mental Health Mosaics

Mental Health Mosaics

Identity and mental wellness

Our identities and how we see ourselves as individuals and as part of a group affects our mental wellness. Maybe we experience internalized oppression. Maybe we don't have a strong sense of self, so we feel untethered. This episode explores the idea of knowing who you are is tied to mental wellness. We speak with psychology professor EJ David, artist Lauren Stanford, and community member Dana Hilbish.

See Lauren's art and follow prompts to explore your own identity at the Mental Health Mosaics website.

[00:00:00] Anne: Welcome to Mental Health Mosaics from Out North, an arts non-profit located in Anchorage, Alaska on the unceded traditional lands of the Dena'ina People. I'm Anne Hillman.

What words would you use to describe your identity? Would you talk about your culture? Your job? Your religion? Your body? And when you talk about who you are, do you think about the here and now or is your identity still rooted in the past?

Like I was a really fat kid and the world wouldn’t let me forget it. In the second grade, the gym teacher took me out of regular class so I could walk laps around the cafeteria. My mom and I went to a weekly educational program specifically for fat kids.

As an adult I fully recognize that these interventions were meant to help me but they were so, so embarrassing and definitely affected my mental health. I was filled with shame and started hiding candy around my room. And I still identify as a fat kid even though now I’m middle-aged and pretty average.

EJ: Our identities are complex, ever-changing things. And how they relate to our mental wellness is affected by both internal and external factors. This is especially true when we talk about discrimination and oppression, which we know has very negative effects on our mental health for many people, oppression can become so deeply internalized that, that it can exist and operate within us. Um, even outside of our awareness in sanction or control.

Anne: That’s EJ David, who like all of us, has many identities. I'll let him introduce himself.

[00:01:48] EJ: My name is EJ David. I am a husband, I'm a father. I am a Filipino immigrant into the United States. I've been living in Alaska now for 28 years. And I work at the university of Alaska Anchorage as a psychology professor but I work for the community

Anne: EJ spends a lot of time thinking and teaching about internalized oppression. internalized oppression includes all the ways that society at large can make us feel terrible about our own identities, be it our race, or our gender, or our body types. Understanding it can help us understand ourselves and others.

So our world is full of, uh, negative and inferiorizing messages, uh, about certain groups of people, certain social things. Um, throughout history, you know, many groups of people, uh, are inferiorized.

Many groups of people, you know, have been oppressed for many generations now. And, you know, when such oppression, such inferior rising messages that, you know, that that is around us, that primary that permeates our society. You know, when, when such thing. Seep into us and infiltrates our minds and our hearts.

That is what internalized depression is. You know, it is a condition when oppressed peoples succumb to the inferiorizing and oppressive messages.

That is propagated by society. You know, the inferior rising messages about themselves and about their group, about their community and, you know, succumbing to such messages, such oppressive messages, no can look like eventual acceptance of the alleged inferiority of one's group.

Or it can look like just, you know, more surface level tolerance and adjustments in order to survive in an oppressive society. So that's a very general definition of it. What does it look like? You know, um, in everyday life, uh, So for me, I've struggled with it, you know? So what I, what I always tell people is that, you know, cause I, I study internalized suppression that's, you know, that's my, my thing.

When I talk to people about it, you know, I am always, you know, I, I make it a point to be. You know, open about my own struggles with it both historically, and even to this day. Like, even though I've been doing work on it for many, many, many years, you know, and even though I've been talking about it for many, many, many years, you know, I still struggle with it to this day.

Right. And so historically the way it's looked for me and for many people, um, I think also is very similar to my experiences, um, is that I, you know, I struggled with a sense of, uh, inferiority, um, As a Filipino person, um, you know, I grew up feeling embarrassed and even ashamed of, of my Filipino ethnicity and culture.

Um, got to the point where I tried to erase it. Um, you know, because I really just wanted to fit in so bad. Like I wanted to really shed myself of anything Filipino. Like I wanted to, you know, forget the language. You know, I wanted to learn English as best as I can and wanted to get rid of my Filipino accent when I spoke English.

I remember growing up as a kid seeing skin whitening products, being shown on television in the Philippines and skin whitening products, uh, you know, all over the grocery stores like aisles and aisles of them you know, in the message that I received there was, the lighter skinned you are the more attractive society will see you and, and, yeah, the more advantageous it's going to be for you, you know, you probably, uh, get accepted more, uh, get hired for better jobs, get paid more, I've associated whiteness with success. In my journey, you know, as I learned more about this, I learned that I was not born that way. You know, I was not born in. I want to be light-skinned gene you know, I, that was not instinctual. I don't have a genetic predisposition to, you know, to wanting to forget my language or to feeling ashamed of my heritage. You know, I was taught those things, you know, those, those attitudes and behaviors were learned. I learned that, you know, it's, it's the history of colonialism and the continued, you know, propagation of these messages.

[00:07:13] Anne: So how does one recognize that within themselves?

EJ: Yeah. You know, it's, it's, it's a tough thing, right? Um, well, one, you know, you need to do a lot of questioning. So for me, you know, I got to a point, um, it was actually around my junior year in high school. Um, and by that time, you know, I really did not want anything to do with my Filipino heritage. I distance myself from other Filipinos, especially other, um, like newly arrived, Filipino immigrants. Um, you know, who I thought were still kind of to Philippina for me because they, they just got here.

You know, they still struggle with English or if they spoke English, they still spoke here with this strong Filipino accent. You know, it just hearing it made me feel embarrassed and ashamed. So I don't want to be a part of that. I was like really separating myself from, from the Filipino community and, you know, I wanted to just be American.

[00:08:16] EJ: I played basketball in high school. Basketball was my first love.

[00:08:21] Anne: And you grew up in Utqiagvik?

[00:08:23] EJ: Yeah, I grew up in Utqiagvik like yeah.

[00:08:25] Anne: Very basketball.

EJ: Very basketball, crazy town. Yeah Whenever it's a game day, the spirit squad they decorate the players' lockers. They put stars and posters or whatever, and then people can write whatever they want on it, you know, like good luck tonight, you know, or, encourage us the players, right. And during one of our class breaks, you know, I went into my locker to get stuff. And then I saw one message and said, you're Filipino act like it.

That was a turning point for me because it made me think about okay so one how am I not acting Filipino?

And then two, like how have I been behaving, toward other people, so that was really the beginning for me, you know, of me questioning, uh, my behaviors and my attitudes about my Filipino identity.

So yeah. So going back to going back to your question now, you'd like this journey of addressing internalized oppression, right? That's the beginning for me, like I started thinking about it, like, okay, I see it. You know, I, I have been you know, feeling this way about newly arrived, Filipino immigrants. I have been trying to get rid of my Filipino accent, you know, I've been just wanting to be American, so that's the beginning of the journey for me, you know, just learning more, learning more about my history and my people's history. Um, also understanding then, you know, as in that process and, you know, realizing that, that it was not unique. The more I learned, the more, um, I realized that there were other Filipinos who had the same identity struggles as I did, and that, you know, many other Filipinos generations before me also had the same struggles as I did.

And then I realized the more I learned that it's not even just a unique to Filipinos, you know, that many other, you know, uh, communities of color, you know, experienced similar struggles and then it's not even just, you know, uh, communities of color that experienced it. You know, other historically marginalized groups have experienced similar identity struggles as well.

The interesting thing about this whole journey was that, you know, in the process of quote unquote. For a lack of a better term right now, like decolonizing my mind. I became more connected to more people, the interesting thing about this slash sad is that to me, that the common thread between all of us is the shared experience with oppression and this shared struggle with internalized oppression.

You know, and as much work as I've done both professionally and personally, to try to address internalized oppression, I still struggle with it. I know that it's still in there and that it still can, can automatically impact, um, my attitudes and behaviors about certain things.

But it's almost like tying your shoe laces. So, you know, none of us are born knowing how to tie your shoelaces. We were taught to tire shoelaces, but because we do it so much eventually now we just do it automatically. And if I ask you right now, can you unlearn how to tie your shoelaces

or try to learn to tie them in a different way?

Yeah. Right. It's really hard.

[00:11:52] EJ: Yeah. So to me, it's kind of like that, like for many of us we've internalized the oppression that we've experienced so deeply and it's become so automatic. For us to think about our identities a certain way that even though we try our best to try to unlearn those inferiorizing attitudes, automatic attitudes that we have about who we are.

It's still there. And so it's, it's, it's almost, I don't, I hate to seem so hopeless, you know, that, that is that it's forever going to be there, but, but to me, at least for me, you know, I don't think I'm I'm 100% going to be able to get rid of it.

[00:12:41] Anne: Are you more aware of it now?

[00:12:44] EJ: Oh, Definitely. And I think becoming aware of it as a huge step towards this journey, because it's so automatic, if we deny it or if we ignore it then it's just going to continue to operate within us and impact us.

Without us even knowing it. And so I think bringing it into our consciousness, acknowledging that we have internalized oppression or we have certain biases within us, is a critical first step because once we bring it into our consciousness, then, then we, I think are more likely to be able to, um, control it, um, and be more critical about. And you know, not have it impact our behaviors toward other people, um, in a, in a bad way.

[00:13:30] Anne: Oh, interesting that you phrase it. I have a S have it impact our behaviors towards other people versus towards ourselves?

[00:13:37] EJ: Well, yeah.toward ourself too. Yeah, because yeah, so here's the thing, right? when we think about internalized oppression, oftentimes we think about us oppressing our own cells, which is.

Right. Um, that is a big part of what internalized oppression is, you know, whether that'd be, you know, feeling ashamed of our identities or, you know, people, you know, like me, for example, trying to get rid of my Filipino language, you know, or some people will use skin whitening products because it's directed toward our own selves and our own bodies.

Um, but you know, a big part of internalized oppression is also how we treat other people. So it's internalized oppression is interesting in that way. Um, and that, you know, it's not just focused on our individual selves right earlier. I said, I started discriminating against other people who are newly arrived, Filipino immigrants.

You see what I'm saying? So that's a radiant example of how my own internalized oppression has gone beyond just me and now has impacted how I behave toward other people

I think is important for us to make a connection between our internal struggles, you know, like these mental, you know, identity, confusion, you know, the things that I mentioned earlier, make a connection between that and external factors like societal factors, you know, don't attribute it to something within yourself.

Right. So make a connection between societal factors and how you're feeling inside, right? Your mental health, your mental wellbeing. That's an important connection that we need to learn to make.

[00:15:13] Anne: Do you ever get the pushback from people who are. You're just blaming others, others, and you're not taking personal responsibility. Like, look, I feel like I hear that a lot, a lot that we all need to take personal responsibility for where we are in life, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera.

Yeah. And that's an important thing, you know, I'm not, I'm not, I'm not saying that people don't have.

You know, personal agency, um, because we do, we definitely do, by the way, that's a very Western concept by the way. Yes. Yeah.

So it's kind of like, how do you, how do you have that conversation where someone is coming in with the viewpoint of yeah.

[00:15:50] EJ: Yeah, but even people who study. Internal, you know, individual level factors for a living like the experts on genes. For instance, we'll be the first people to acknowledge that it's not all about genes, that our environment has a big part in how we turn out as well. Right. And so, so yeah, so I'm not, you know, I'm not saying that people don't have personal agency and I'm not saying people should not have personal responsibility, but I think, so much weight has been put on that.

And to me that's dangerous actually, you will live in a world where that is, I think, overly valued, this personal responsibility and individual agents who we do have those things, and those are important things I think, but I think we can not just fall on that because if we do that and this has been going on.

What's been happening in our society. Is that what ends up happening is we end up blaming people for their own oppression. you know, it's called a victim blaming is what it is. Once you individualize, um, what are otherwise societal issues like clearly societal issues, but then you individualize it.

Then what you're saying is that nothing in society needs to change. It's just a few struggling individuals here and there. So then it's their problem only. So it's, it's them who needs to change, not us. And what I've found is that people who are saying that, who tend to say those things that, you know, you should need to take personal responsibility are, are, are people who tend to be in positions of power and privilege. 'Cause they're the ones who don't want the system to change because the system has been benefiting them. Right. They've succeeded in the system. So why the hell do they, would they want to change the system?

You know, I've said it a few times already today is that, you know, wanting lighter skin. I wasn't, you know, don't have a gene, you know, so, you know, it's, it's really to, you know, to underscore that point and to kind of anticipate that response from people, right. That, that, that response of well don't you have like individual level factors or individual mechanisms within you, you know, that, that will, I'm like, yeah, of course I do.

Of course they do, but that's not the only thing that matters. You know, and when it comes to this, I don't have individual level factors. that makes me want to lighten my skin. You know, that makes me feel ashamed of my culture and my heritage.

So making connections, you know, going back to what I was saying earlier is the me making connections is important because. You know, so, so that, you know, making understanding that there is a connection between external factors, societal factors in how I feel about myself and my, you know, my, my community is important, but then also making connections between, you know, my experiences and my struggle with the experiences of other people, as I mentioned earlier is huge because it tells me that no, I'm not unique I'm not an isolated case.

You see what I'm saying? That this is widespread. Right. This is a widespread problem. It's a worldwide problem. It's not just me. It bolsters that argument that it's not just an individual level problem, right. That many people have felt this, you know, throughout the country and throughout the world.

Right. So, yeah, so making that connection and also the third connection that I think is important to make is that this is not new, right? This is not just, you know, a contemporary modern struggle, you know, that many of the things that we're seeing today, many issues that people are struggling with today have been happening for generations, you know, for, for, for pretty much throughout history, you know?

So also making that connection between, you know, historical stuff and what's happening now, right? So like, you know, slavery that happenedyou know, many years ago, that's still has implications today. Colonialism that happened many years ago still has very real implications today.

[00:19:58] Anne: It's still happening.

[00:19:59] EJ: to me you know, learning those connections and making those connections, is empowering. So even though we may not be able to, like I said earlier, address the internalized oppression within our own selves.

Making those connections, I think will help us make significant steps toward addressing oppression itself. So even if you know, it's impossible for me, To completely 100% erase, internalized oppression within myself, by working to, reduce oppression then perhaps my children will not develop internalized oppression.

So, so yeah, so that there's the hope.

[00:20:48] Anne: That's a great, wonderful hope to end on. Thank you.

[00:20:52] EJ: Thank you.

Anne: That was community psychology professor EJ David talking about internalized oppression.

Internalized oppression can shape how we view ourselves in relation the world and it can be a force that molds our values system. Our values guide the way we interact with others and are a key element of identity. So what happens if don't feel like you have any values? How does that affect your mental health?

[00:21:21] Dana: The values that I was following weren't mine per se. Like I lived, if I lived with a man, I would follow his values. Um, my thoughts on, how am I supposed to do this? I would revert back to my grandfather normally, or possibly my parents, but it was never, how do I want to do this?

[00:21:44] Anne: That’s Dana Hilbish, a member of the Mental Health Mosaics' advisory board.

If you listened to our episode about long-term recovery, Dana’s voice will be familiar.

Dana had to go through treatment for alcohol addiction before she could start figuring out her personal value system. Before that, she was adrift in the world.

Dana says it was just easier to mimic the people around her than instead of trying to figure out what was truly important to her. At the time, she also believed that women and their opinions weren’t as valuable as those of men. She drank to avoid dealing with her emotions about her life and past traumas.

[00:22:28] Dana: I numbed myself. There was never a good reason not to have a drink and my emotions and my, my thought, my thinking patterns. If, if they got too convoluted in my head, I would just drink it or drug it away or find another relationship to focus on so that I didn't have to think about it anymore.

Or I could just follow someone else's thinking and I didn't have to try and work it out on my own.

[00:23:00] Anne: She says she lacked self-respect and she didn't want other people to think badly of her, so she avoiding forming and sharing opinions on anything.

politics, religion, uh, relationships, boundaries within relationships, you know, I just would drink it away and that, and didn't have to be an issue anymore or, you know, I would find some way not to have to think about it.

And, um, it's because controversy meant that someone else wasn't going to like me most likely. Or I was, you know, I was going to have to stand my ground and I just, there wasn't enough of me to stand on I had, they weren't my values,

Eventually Dana ended up in prison. It took five years before she finally admitted that she needed to go into treatment and learn who she really was.

What did it feel like when you were like, I, this, I don't know what I believe.

[00:24:11] Dana: I was frightened. I was kind of embarrassed. Like, oh my God, you know, I was, I was frightened. I was embarrassed. I was, I did not know what to do next. You know, fear of change is a biggie. Some of these things. I hadn't changed them along the way.

When I finally got to that point where I looked at myself kind of from the outside and said, how, how did you, how did you get there? You know, I could see why I had kept on going and, and I could say, okay, you don't need that anymore. And I can feel safe about that. And so what do you do when you let go of a behavior or a thought, then you have to have something else to replace it with. Well, what if you don't have something else that you firmly believe in at that point? It's hard to just sit and be one with yourself in a, in a floating situation like that.

Anne: Over time—and with the help of a 12-step program—Dana evaluated her actions, forgave herself and others, and connected to a higher power. She learned that she had to heal from her past and accept help. She also had to figure out what she really believed so that she could move forward steered by her own values and identity.

Dana: I once was a very lost human being and I was unkind to others and mostly even myself. I managed to turn that around and I find value in my gender. I find value in my sobriety. I find value in other people's opinions that they are other people's opinions and they don't have to be my own.

I'm grounded in a way I never was. And I have a set of values that, um, I have practiced for a while and I'm going to keep them because they work for me and they're healthy and I know where they came from.

And if some of them were someone else's at one time, that's okay. But I know that they work for me too. When you chose them, I chose them. Yes, I did. And I am willing to defend them,

Anne: Dana Hilbish now knows that she is many things. She's a gardner, a dog trainer, a supportive friend, a feminist, and...

Dana: I am a woman in recovery. I believe if I put my sobriety first, then I will be able to handle whatever comes down the pike. I believe that there is joy to be had in spending time with others and, sitting in a room, being there for others, listening to them. But I don't have to believe what they believe, I am worthy of myself. I am worthy of the thoughts and feelings that I have today. And, and that is enough.

Anne: Mental Health Mosaics is more than a podcast. We're also using art to explore mental health.Visit our website, mental-health-mosaics-dot-o-r-g, to view visual art and read poetry about mental wellness. You can also download worksheets and read prompts that will help you create your own pieces that explore mental health and, we hope, start on your own path toward wellness.

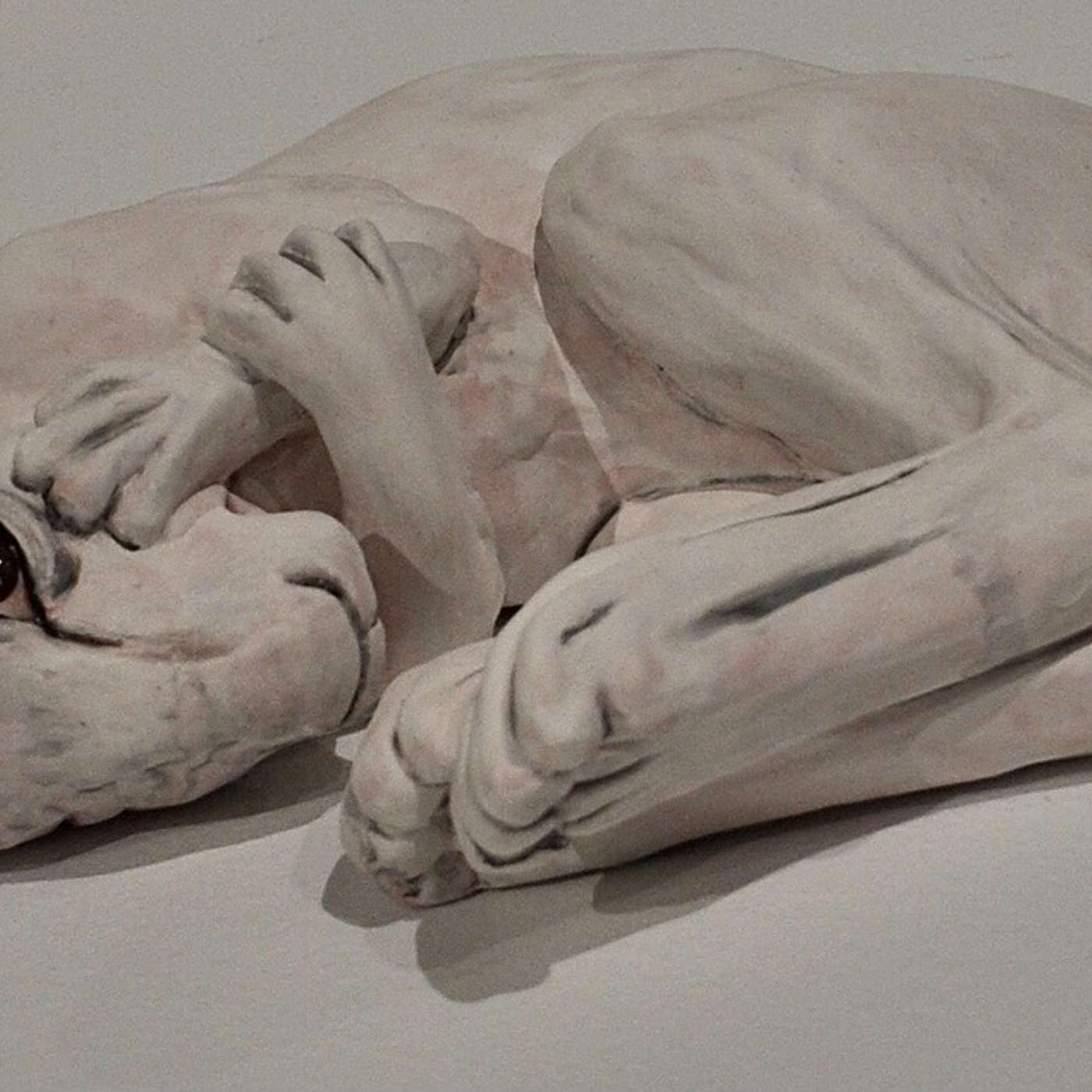

One of the artists featured in the Mental Health Mosaics spring 2022 art show in Anchorage and online is Lauren Stanford, who crafts animals out of clay.

[00:28:18] Lauren: My name is Lauren Stanford. I'm a lifelong Alaskan. I'm a commercial fishermen and I'm an artist.

I am part Yup'ik and I identify as such, but I'm also, you know, I've got a lot of European heritage too.

I used to actually sculpt kind of unusual, but familiar animals because I felt like I really didn't belong in either group and, and, um, 'cause I felt like I was born. I was born and raised in more of a Western world, but then I also, you know, spent a lot of time in Bristol bay and, you know, I definitely have this Yup'ik heritage.

And part of the fishing is, is commercial fishing. And subsistence fishing is very important to me because it's kind of my last link to that heritage. And so I feel like I'm somewhere in between, um, two worlds in some. That's the best way I can describe it.

[00:29:18] Anne: How does that end up playing out in your artwork?

[00:29:21] Lauren: I used to sculpt kind of unusual animals, um, just because I felt like I didn't really. I was kind of my own species in a way, for lack of a better word. Um, I was always drawn to these animals that looked very familiar. Like for instance, there's animal called a main Wolf. It's this very long legged fox-like creature in South America.

And I made a sculpture of that once, because it looks like a Fox, it looks like a Wolf, but you really don't know what it is. And. I've I've had people wonder what my heritage is, is, you know, cause I'm very tall. Um, but I also have this very Scottish skin, very pale, but then I also have these kind of more native features in my face.

And so I've either had people ask me, you know, what my background is, or they've got more, oftentimes they'll ask people who know me, but they, you know, they don't ask me directly. They have this roundabout way. And um, so it's, it's kind of this idea of. People don't really know who or what I am. And so I can connect to these animals that look like something familiar, but not.

And so for awhile, I was making kind of these unusual animals. I went to California in fall of 2018 for an artist in residency. And while there I started making this hairless Guinea pigs, and it was an animal I saw was in school, up here in Anchorage and just never had the time to pursue, but I would move to this new place.

I was feeling strange and vulnerable. And it's really fun to sculpt wrinkles. So I started sculpting these, these hairless, Guinea pigs, and they've really kind of took on this identity of the most vulnerable and strange part of myself. And so I used them as kind of these fun and whimsical characters to actually explore and express kind of the saddest, darkest parts of myself. And they've really started becoming these characters that people responded to. And, um, even though a lot of times people didn't know what they were, which is fine. A lot of people don't know what I am. And so it kind of tied into that. And, um, I haven't, I haven't made any recently.

The Guinea pig served as a way to start a conversation with people that, um, was definitely more approachable, uh, than perhaps some of the content. And I think a lot of why I sculpt animals, there's multiple reasons I sculpt animals, but animals kind of are this almost safer vehicle to talking about things that can be uncomfortable to talk about such as your mental health or really tough experiences you've been through. And so long story short, unusual animals to kind of, um, explore this kind of. Side of mice, you know, not knowing exactly what or who I am. And now that I've moved back to Alaska, I've recently started making more Alaskan animals and I started sculpting them and when, at the end of my residency, because I think I was homesick and it's kind of one of those things where you, you leave the things, you know, because it's almost like sculpting a moose almost felt like making some. Like a tourist trinket to me when I was living up here and then I leave and I start really missing the familiar things and they start bringing on new meaning when you're away from them.

And so I've started sculpting animals that are more, um, that are all Alaskan animals that I've just kind of had this new appreciation for us since I've been away.

[00:32:58] Anne: That makes a lot of sense. for folks who haven't seen your artwork yet? Yes.

Describe some of it to us.

[00:33:04] Lauren: I tend to make larger scale. Animals, depending on what equipment I have access to. So if I have a big kill and I'm going to try and build something as big as I can to go in it, and that used to be coming from a place of feeling these monumental feelings and feeling like the only way that a viewer could really understand what I was experiencing was making it as big as possible, because it feels huge inside of me.

And this is the only way that I can express it. And since then, I've kind of. Uh, taken a step back and thought more about content in the way of. Interacting with a viewer as opposed to just scale. Um, so I talked earlier about these hairless Guinea pigs. I made, uh, I, I tend to finish my animals either with house paint if they're really large, they have more of a matte appearance. If they're smaller. I feel safer to go through a whole firing process. I like to do a lot of layers with my colors. Um, I like to build up the color stories in a way that I might start with a layer that, uh, if, if an animal's white, maybe I start with yellows and pinks and then build up those layers.

So that from far away, it looks like it might be a white animal, but you get close and there's all these dynamic colors. And I use a lot of drips in my work and. And the drips kind of represent the tears.. Cause a lot of these ideas come from really sad and lonely places.

And for me, while working in adding these colors and using of water and whether it's with a house paint or the underglaze watching that color kind of move, or the form is a very cathartic and calming part of my process, because especially when I'm building something large, it's stressful, there's a lot of engineering that goes into it. And then that's, that's just The whole process of going from the soft malleable clay and creating the structure that is fired really alludes to the whole self process self-expression exploration process I go through of creating something that it's like a more permanent and stronger version of myself after each.

And so these animals, oftentimes they're not, they're not hyper-realistic they definitely go through, I guess the filter. That is me. Um, so they're, I, they kind of are a little bit cartoony in some aspects, but I'm kind of, I don't know. I don't know how to describe my style. I feel like my animals kind of, they're not cartoony, but they're not super realistic.

There's somewhere in between.

It's kind of like using these animals as this vessel of that they're not anatomically correct, but they contain all the realness I can put in them, emotional realness if that makes sense.

[00:35:52] Anne: So you've kind of hit a little bit on how, how your art is this cathartic experience for you, um, and how it helps your own mental health. Yes. Um, I'd love for you to tell me a little bit more about how you were exploring mental health in general, through your art or emotions through your art.

[00:36:14] Lauren: Oh, they go hand in hand. Um, so you, you mentioned the slow Loris. So the slow Loris was part of a series I did on the different stages of grief. I had recently lost a very important, loved one in a traumatic accident. And I didn't know what to do. I didn't know how to cope with it. It was an event that I think changed my family and.

I look at some of my family members. It's like, how are you still walking upright? But we all cope in different ways. Right? And for me, my artwork is what keeps me whole, and part of this body of work, I kept thinking about my loved one that I lost. And it was like, what would he think is cool? What would he like?

And during one of my check-ins, it was, um, with the BFA communities when I was in the BFA program at UAA. Um, Alvin Amos in he's a pretty renowned local artist who was one of the advisors on the panel. And I was talking about how I was, you know, thinking about what would I love, one, like, what would he, what would he think was neat?

And his, like any told me it was like, I was keeping a dialogue open with this person that I loved.

So in that way I was keeping my loved one that I lost alive. And. Oh, I didn't think I'd start getting. Um, and so that gave me hope when I was feeling very lost with health. This person was so important to me.

And I think in any situation in which. I'm feeling self-doubt I don't know what to do with my life. I don't know where I'm going. I don't know what my purpose is using my art to explore that kind of clarifies that in some way. And it gives me purpose in that moment of making. And so the slow Loris was the, the, uh, stage of grief of depression

so I ended up building it so that it looked like it was in a cage, but the stripes are painted on that.

You have to stand in a very specific spot in order to see those stripes, to see this idea that it is in a cage because when you are in the throes of depression, unless you've been there, it's hard for other people to really understand, unless they're, they've been there or there they're standing in a spot to really fully understand it.

If you're standing off to the side of it, it just looks like it has these kind of weird Bob, so color on it.

But when you stand directly in front of it, suddenly those bars shift into place and you can understand what it's going through. And so that's what I was trying to emote with this piece

Because right now I feel so alone and isolated. And so that's what my work is always trying to do is trying to find a way to connect to other people. The things that make me feel so alone and so isolated, and these animals are these door.

Like they're kind of this way of me feeling more comfortable talking about, um, feeling depressed or anxious or alone or hopeless with. Um, at the very least a viewer or someone else, like they'll walk up this animal and, you know, they'll connect to something in it. And if I happen to be there, we'll have a conversation.

And so it creates this connection that wasn't there before. And with each connection, I feel less alone, less isolated, more hopeful, feel more purposeful. And it's amazing. The things that I think, you know, people talking about mental health, it's getting better and better, I believe. Um, but it's oftentimes just really uncomfortable because you know, sometimes, most of the time people don't want to focus on the things that are hard to talk about that make it hard to get out of bed every day.

But we all go through it. And just different stages, whether that is, um, like a mental illness we're born with or a situation that causes a lot of stress and anxiety, or, you know, it's, it's, whether it's something we're born with or something that evolves over unfortunate circumstances, we all go through it in different ways.

Or we know someone who has. Um, I know I grew up with people in my life that struggled with mental illness and seeing their struggle made me have the resolve that I need to do everything I can to remain healthy for those that I love. Cause it's really hard to see loved ones struggle with their mental health.

And so finding ways for me to cope in a way that is healthy and productive. And that is what my art has become. And so it is self-healing and I feel like it is healing. Whenever I have a conversation with someone about my work, it's like, okay, you feel that too, you and I are less alone now.

[00:41:26] Anne: when you submitted your work, it was. W in association with the topic that we're exploring about identity and mental health. can you share a little bit about how you see the two being connected? You talked a little bit earlier about like your Yup'ik identity and your white identity and the conflict there.

Are there other ways that you feel like mental health and mental wellness and wellbeing are tied with identity

[00:41:48] Lauren: I feel as though, um, sometimes people get judged or labeled based on their mental health and where they are. And that is not the entirety of who someone is, is just a small part of the cool that is them. You know, I I've had my own dealings with depression and anxiety and. Um, but that is not who I am.

It influences the work I make. And sometimes my day-to-day habits, but it's not who I am. The older I get. I'm I'm so fascinated by how complex people are. We are, are literally bits and pieces of our own experiences in the world we're living in and, you know, Sometimes, you know, I think for some folks mental health, when they're struggling, it feels like a bigger part of that picture for them that it's influencing their day to day.

And then it influences who they are, but it's not all of who they are.

[00:42:54] Anne: It feels like from what you've been talking about, that at this point, you're at a place where you know how to heal and how to work through things through your art.

How did you get that?

[00:43:09] Lauren: A lot of therapy, a lot of talk therapy. Um, I don't know that I would've gotten to this part of my journey where I can so to speak self-heal um, because I'm not gonna rule out that I will never have to go back to therapy. Um, Being able to talk to an objective person who is on your side of, of being well and whole is, was very important for me to be able to process a lot of things that have happened throughout my life and to understand them.

It was such an important part of my process of kind of coming out of the darkness and seeing my self worth and my value in this world. And, um, having that encouragement and just being able to talk through things with someone, but finding someone, whether that is a licensed therapist or someone who is emotionally available . Cause you also don't want to like have a friend that you're constantly putting your own baggage on because they have stuff going on too.

But everyone deserves to be heard and to be understood. Yeah. Um, to have tools, uh, to help navigate life.

That was Lauren Stanford talking about her work and how identity is tied to mental health. You can see her work on our website, mental-health-mosaics-org and checkout her website laurenestanford.com.

This episode was edited by Jenna Schnuer, mixed by Dave Waldon, and produced by me, Anne Hillman. Our theme music is by Aria Phillips. This project is funded by the Alaska Mental Health Trust, the Alaska Center for Excellence in Journalism, and the Alaska State Council for the Arts as well as generous donors. You can support Mosaics and keep this podcast running by going to our website, mental-health-mosaics-dot-org, where you can also find other mental health resources. Want to help other people find this podcast? Rate us on any and all podcast apps!

Thanks for listening and be well.